Believe it or not, there was a time when Broadway was merely the name of a street in New York City. The “Great White Way” as it is universally known today was little more than a meandering former Native American pathway stretching from Bowling Green near the southern tip of Manhattan Island to Inwood at its northern reaches. The city’s fledgling theater scene got its start in the mid-18th century as modest play houses began opening along Nassau, John, and Chatham Streets in what is now the Financial District.

As New York’s population swelled in the decades following the Revolutionary War, theaters were constructed to follow their northward march up the island. For the most part, the play houses were clustered along the Bowery, which was for many years the city’s busiest commercial and entertainment thoroughfare. But 1823 also saw the opening of Niblo’s Garden on Broadway near Prince Street in today’s neighborhood of SoHo. Niblo’s originally opened in 1823 as a cafe and coffeehouse, but after a fire destroyed it in 1846, it was rebuilt as New York’s premiere theatrical venue. Niblo’s could hold 3,200 people and boasted the more technologically advanced stage equipment in the city. It attracted the leading actors and performers of the day and reserved a place for itself in the annals of global theater when, in 1866, it staged “The Black Crook,” which is today recognized as the world’s first true musical.

A map of the west side of Broadway, ca 1920, showing the large collection of theaters it boasted.

(NYPL Digital Gallery)

By the time Niblo’s was demolished in 1895, New York’s theater district had long ago migrated north to Union Square and were beginning to gather around Madison Square near 23rd Street. The continued to leapfrog ahead of the city’s burgeoning population (and its accompanying high real estate prices) and by the first decade of the 20th century, theaters began to spring up on and around Longacre Square. When Adolph Ochs, publisher of the New York Times newspaper, moved his company’s headquarters to a new tower overlooking Longacre, he persuaded Mayor George B. McClellan, Jr. to built a subway station there, and to thusly rename Longacre Square “Times Square.”

Times Square, ca 1910, with the New York Times Building featured. The building still exists, now covered with advertisements. Every year, the Ball is dropped on its roof.

(NYPL Digital Gallery)

As the financial fortunes of New York’s increasingly massive population continued to improve in the new century, technological advancements such as electric streetlights made the city increasingly safe to traverse at all hours of the night. Theaters and playhouses multiplied upon themselves in pursuit of the vast profits to be made from this new and immense pool of potential patrons.

The massive Hotel Astor had been constructed on Broadway on the south side of 45th Street in 1904, with its 1,000 guest rooms providing a never-ending stream of visitors looking for entertainment in this new and glittering playground district. In an attempt to take advantage of this potential gold mine, theater producers Wagenhals and Kemper constructed “The Astor Theater” directly across the street from its namesake hotel. Its 1,600 seats opened to the public on September 21, 1906.

In 1909, the Astor gained a neighbor in the Gaeity Theatre, which could hold 811 theatergoers at the corner of Broadway and 46th Street. The Gaiety was designed by renowned theater builders Henry Beaumont Herts and Hugh Tallant, who had already won praise for their 1903 New Amsterdam Theater as well as the Brooklyn Academy of Music in Fort Greene.

Herts and Tallant were again called into action in 1911 when producers Henry B. Harris and Jesse Lasky set about trying to enter the burgeoning Times Square entertainment industry. On the south side of 46th Street, just west of the Gaiety Theatre, Harris and Lasky opened “Folies-Bergere,” an attempt to bring risque Parisian nightlife before puritanical American eyes. Folies-Bergere introduced the concept of interactive dinner theater to the city’s theatergoers, replacing the traditional rows of seats with a collection of small round tables. Actors and burlesque performers would venture off stage and into the crowd, bringing the act directly to their viewers. One such performer was 18-year-old Brooklynite Mary Jane “Mae” West. Her show “A La Broadway” folded after just 8 performances, but Mae West received a glowing write-up in the New York Times, which catapaulted her to a stardom which would endure for more than 4 decades.

But perhaps America wasn’t ready for such a bawdy display of European revelry, because Folies-Bergere closed after just 6 months. The building would not remain vacant for long. After remaining dark for about a month in September and October of 1911, it reopened as the more traditional 895-seat Fulton Theatre with a staging of the play “The Cave Man.” The Fulton screened motion pictures in 1915 and 1916, but otherwise remained a straight-laced Broadway theater for decades.

The corner of 45th and Broadway in 1936. The Astor Theatre is front and center, with the Gaiety to its right (renamed Minsky’s Burlesque) and the Bijou and the Morosco to its left.

The Astor, Fulton, and Gaiety gained two more neighbors in 1917 with the opening of the Bijou and the Morosco side-by-side on 45th Street directly to the west of the Astor Theatre and across the street from the Astor Hotel. Both play houses were financed by the Shubert brothers, Jacob and Lee, who were busily assembling the greatest theater empire this nation had yet seen.

“It is none of your little theaters,” the Times reported on February 5, 1917, the Morosco’s opening night, “but a spacious one that has seats for 905 and standing room for many more. It is comfortable and an attractive color scheme of gray and purple greeted its first audience after they had passed through the lobby.”

Two months later, on April 12, the Shuberts christened the 603-seat Bijou Theatre, sandwiched between the Morosco and the Astor. The Bijou was originally devised as the “Theatre Francaise,” meant to feature French stage classics, but that idea was scrapped halfway through construction. Nevertheless, the Bijou retained a decidedly French feeling about its blue, gold, and ivory interior.

In 1925, amid a glut of new theater openings on and around Times Square, the Astor Theatre ceased staging legitimate plays, instead screening movies on a permanent basis.

The Astor’s neighbor, the Gaiety, followed suit in 1926, and by 1932 had rebranded itself as “Minsky’s Burlesque,” becoming one of the premiere burlesque venues in New York. The Minsky brothers, Abe, Billy, Herbert, and Morton, used the Great Depression to their advantage, luring down-on-their-luck pretty girls onto their stage in skimpy, glittery outfits, and then luring desperate-for-a-distraction men into their booths where they happily dropped what little spending cash they had on a few minutes of blissful distraction.

The Depression wasn’t so kind to the Shubert brothers, however, and they lost both the Bijou and the Morosco during the economic ebb. The Bijou flip-flopped between staging plays and being a movie house until it shut its doors completely in 1937. The Morosco sat in financial limbo until finally being purchased at auction by City Playhouses, Inc. in 1943.

The 1940s saw fiery Mayor Fiorella LaGuardia attempt to sweep “smut” out of the theater district, cracking down hard on burlesque theaters including Minsky’s in the former Gaiety Theatre space. For a short time, its owners attempted to revive Vaudeville acts on the stage, but by 1943, the Gaiety had been converted into a movie house and renamed the Victoria.

The Fulton Theatre was fortunate enough to have avoided the disgraces which befell its neighbors during the Depression and wartime years. “The Jazz Singer” premiered there in 1925 before being adapted into the world’s first talking film the following year. Bela Lugosi originated his role as Dracula on the Fulton’s stage in 1927, and Joseph Kesselring’s “Arsenic and Old Lace” was debuted there in January of 1941. The Fulton screened movies from 1947 through 1949, but reopened as a legitimate theater in 1951 with a staging of “Gigi,” in which Audrey Hepburn made her American debut.

Also in the 1940s, the Astor Theatre became MGM’s theater of choice for premieres of its big-screen technicolor musicals. In 1949, prominent modernist architect Edward Durell Stone was selected to modernize and expand the Astor. This modernization included stripping the Astor of virtually all interior decoration, covering its walls with a modernist mural, and removing completely its elaborate gilded proscenium in favor of an immense new movie screen. The Astor’s exterior was likewise stripped of all ornamentation, its facade covered by a slab of unadorned marble and its 1906 marquee replaced by modernist neon box.

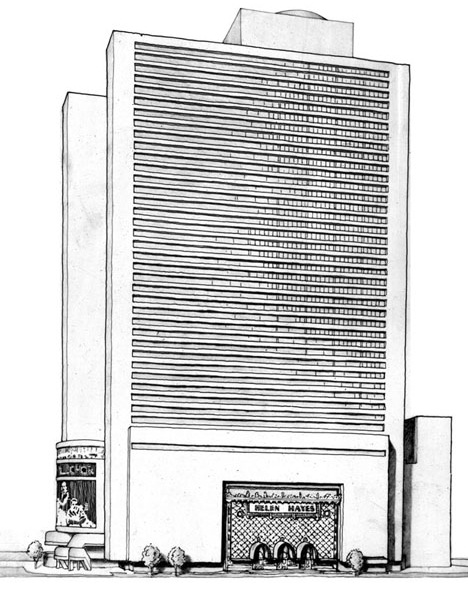

Meanwhile, on 56th Street, the Fulton Theatre was undergoing a renovation of its own. On November 20, 1955, the New York Times announced: “Tomorrow night, Helen Hayes achieves a distinction rarely accorded an artist. In recognition of her fifty years on the stage and her position as one of the nation’s most beloved actresses, the Fulton Theatre becomes the Helen Hayes.”

At the Bijou, the Astor’s expansion had cost is a portion of its stage an orchestra, cutting its seating capacity to just 365. It abandoned the traditional theater world and reopened in 1962 as the D.W. Griffith Theatre, screening art films. It changed names again in 1963, becoming a Japanese film house known as “Toho Cinema.” This, too, proved to be a short-lived iteration of the little Bijou, and by 1965 it was back to its original name, flip-flopping between stage plays and movies before finally settling down as a playhouse in 1977.

The 1970s were unkind to all of New York, and the Times Square theater district seemed to be at the very heart of its downward spiral. As crime rose, fewer patrons felt safe attending late-night shows in the increasingly-desolate area. In 1972, the rundown Astor Theatre finally closed its doors, a victim of bad management. By 1980, the Victoria (formerly the Gaiety) was again rebranded as the Embassy 5 Cinema.

In 1973, it was announced that Atlanta-based hotelier John Portman, Jr. planned to build an immense and modern new hotel complex directly in the heart of Times Square. His intended location: right on Broadway, between 45th and 46th Street. This announcement electrified and galvanized city residents, both for and against the urban renewal project. On the one hand, many people (including those in city government) loved the idea of injecting so much capital and new construction into the heavily depressed theater district. On the other hand, actors, producers, and theater patrons alike decried the loss of 3 functioning Broadway stages along with 2 cinemas.

In all, Portman’s proposed hotel would wipe out more than 2,200 theater seats, excluding the 2,000 more seats that would be lost with the destruction of the Astor and Embassy 5 (formerly Victoria, formerly Gaiety) theaters. Portman assured opponents that he would build a new, state-of-the-art Broadway stage inside his hotel, but the loss of so many square-feet of stage and so much history was too much to endure. The potential loss of the Helen Hayes, the Bijou, and the Morosco brought protesters to the streets in numbers not seen since the demolition of the original Penn Station in 1963.

Susan Sarandon being arrested for disorderly conduct while protesting the demolition of the Helen Hayes, Bijou, and Morosco Theatres.

Actors young and old gathered in protest, sending letters and making phone calls to various members of city government, begging them to “save Broadway.” And for a time, their efforts were rewarded with success: Portman seemed to back down. But in 1980, he came back at his detractors in full force, garnering support from city government including Mayor Ed Koch, who helped to secure financial subsidies for the hotel’s construction. In 1982, the wrecking balls arrived on the block. One by one, the near century-old theaters were reduced to piles of rubble.

Within 2 years, the Marriott Marquis opened, breathing new life into the Times Square area. Such a massive, modern hotel placed right at the city’s center encourage further gentrification of the area. Slowly but surely, theaters have been fixed up, smut has been pushed out, and Times Square has once again become the center of sparkle and excitement for the millions of visitors who pour into New York City every year.

The Marriott Marquis with its main entrance on Broadway, where the Astor and Gaiety once stood. Its long side faces 46th Street, formerly home to the Helen Hayes Theatre.

But what was the cost of this seemingly beneficial hotel project? So many theaters filled with so many seats, smashed into silence in the name of urban renewal. Careers were formed, shows were made classics, and countless memories were made within the halls and auditoriums of those 5 old theaters. And as the years tick by, it becomes increasingly difficult to find anyone who knows what used to be, and perhaps what could have been, as they mill past the hulking 50-story Marriott Marquis. New York is always changing. For better or for worse.

What a wonderful trip down memory lane! It is too bad that the modernization of Times Square involved the demolition of so many wonderful theatres.

Thanks for sharing this. The Morosco, Helen Hayes and even the poor Bijou will always be part of my most cherished theatre memories. It’s a damned shame that they can’t be a part of the memories of future audiences.

Reblogged this on Musings and commented:

Check out this great blog about New York City history! I could read it all day and then some!

It’s horrifying, what these animals have done to the city. Yeah, it’s shiner now, and it’s corporatized and dead. And the destruction of these beautiful theaters is sick. Really, it’s insane. New York was a great city once. Not anymore.

yeah old New York had character, I stayed at the Piccadilly hotel and went to many shows at the Helen Hayes, too bad we cannot learn to preserve our old prize buildings. Just think if in Rome, they tore down ancient buildings so New shiny buildings would be better. so sad.

Thanks for reading! This is something I struggle with while living in New York. Half of me wants everything preserved and frozen in time, while the other have is glad to see the city remain vibrant and ever-changing. The loss of these theaters was a tragedy indeed, but I have to remind myself that nothing in New York is forever. It’s just the nature of the beast. The Marriott may fall one day, too, and be replaced by something spectacular. Who knows? I try to just be a spectator and enjoy the city as it is… For better or worse.

-Keith

I fondly recall one of the later iterations of the Bijou Theater, after it had dropped the Toho Cinema name yet continued several series called “The Films of Japan”. Going there was like taking a class on 20th century Japanese Cinema. I saw t least 50 films there several as double features, ranging from the Samurai Trilogy to most of the modern classics of post WWII Japanese film. That period transformed me from a moviegoer to a connoisseur of cinema. I have never looked back. Thank you, Bijou.

This is fascinating! I was recently inside the Marriott Marquis (its theatre is currently dark) and couldn’t help but feel depressed at the knowledge that so many storied stages fell to be replaced by such a stark building. I’m glad you have such wonderful memories of the Bijou/Toho and hope you pass the stories along. Thanks for reading!

-Keith