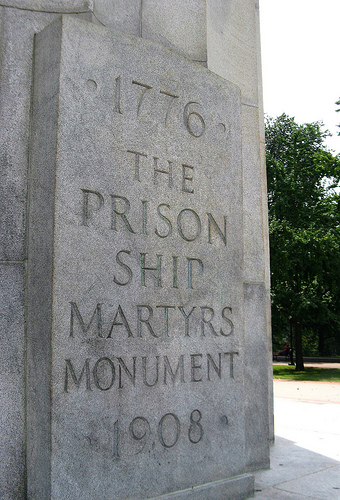

Looming over the trees atop one of the tallest hills in New York City stands a 149-foot-tall Doric column topped by an immense green copper lantern. At its base reads the inscription: “1776 THE PRISON SHIP MARTYRS MONUMENT 1908.” Who were the “prison ship martyrs” and why did they merit such a grand tribute more than 125 years after their deaths? The answers to those questions constitute one of the most sobering tales of this city’s role in the War for American Independence.

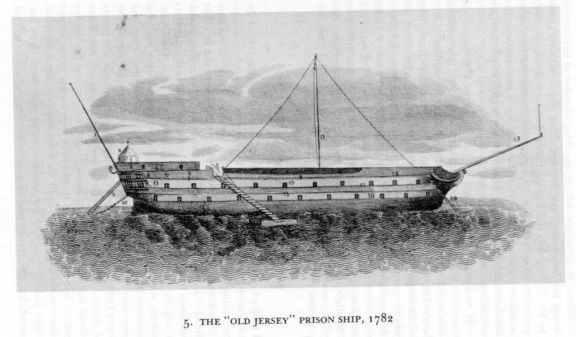

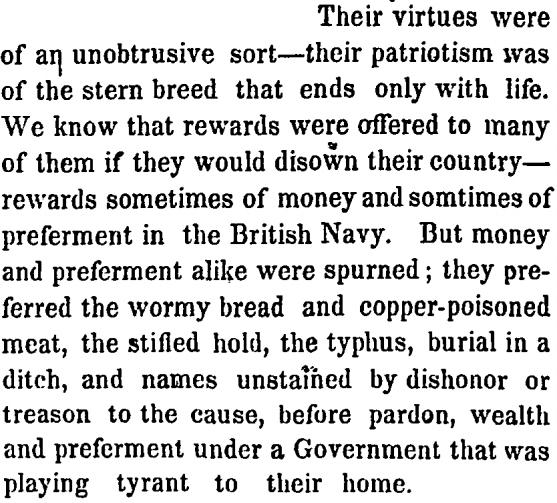

Where the remains of the Brooklyn Navy Yard now sit, awaiting redevelopment amid Brooklyn’s wave of gentrification, there was once a placid little inlet known as Wallabout Bay. In 1771, a British hospital ship, the HMS Jersey, was anchored in the bay to serve the New York and Brooklyn communities.

When the American colonists declared war upon their tyrannical British overlords, the first major military encounter for the two belligerents was the Battle of Long Island, waged not far from Wallabout Bay and the HMS Jersey. George Washington and his 10,000 Patriots were vastly outnumbered by the 32,000 Redcoats which had massed on Staten Island before crossing the Narrows to engage them. Not wishing to endure a slaughter, Washington fled across the East River to Manhattan, where he fought skirmishes ever northward before evacuating to New Jersey and eventually Pennsylvania. New York and its strategically valuable harbor fell into the hands of the British.

The newly-declared independent nation of the United States was not recognized by the Crown as a true foreign entity. This ragtag band of rebels were traitors of the British Empire and would be brought to heel. The HMS Jersey was quickly converted from a hospital ship into a prison ship. Any captured American soldiers and, ultimately, any arrested civilian Patriots were thrown below decks aboard the Jersey, which quickly earned the apt nickname “Hell.”

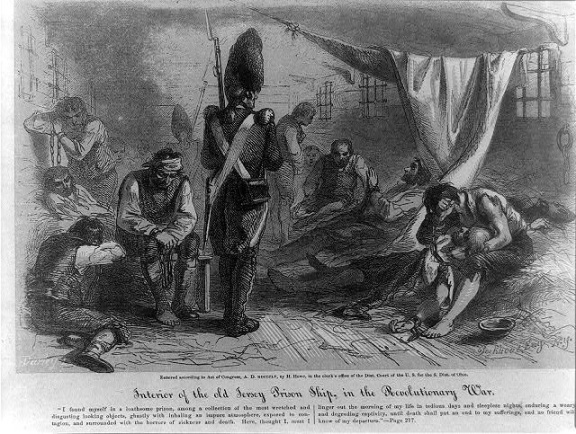

Conditions on board were beyond despicable. Meager rations of maggoty bread and rotted meat left the prisoners sick, weak, and emaciated. With no toilets to speak of, excrement piled up as thousands of men and boys were packed into the ship’s dark, dank interior. Occasionally, groups of prisoners would escape overboard, only to be recaptured on British-held Long Island. As years slipped by on the Jersey for some prisoners, life became unbearable: unable to wash but with saltwater, their skin turned sallow and hung over their skeletal bodies like old parchment. All thought was consumed by plans for escape, when not distracted by want of food or drink.

Captain T. Dring, who survived imprisonment on the Jersey, discussed the prisoners’ celebration of July 4th on the ship. They stored rations for the celebratory occasion, and during their daily furlough on the top deck, they ate, drank, and made merry, much to the chagrin of their British captors. Before long, tempers flared, and the Americans were forced back below deck by the Redcoats, who slashed haphazardly with their bayonets in their frustration at the prisoners’ refusal to stop singing patriotic songs. Captain Dring recounts:

“It had been the usual custom for each person to carry below, when he descended at sunset, a pint of water, to quench his thirst during the night. But, on this occasion, we had thus been driven to our dungeon three hours before the setting of the sun, and without our usual supply of water. Of this night I cannot describe the horror. The day had been sultry, and the heat was extreme throughout the ship. The unusual number of hours during which we had been crowded together between decks; the foul atmosphere and sickening heat; the additional excitement and restlessness caused by the unwonted wanton attack which had been made; above all, the want of water, not a drop of which could be obtained during the whole night, to cool our parched lips; the imprecations of those who were half distracted with their burning thirst; the shrieks and wails of the wounded; the struggles and groans of the dying; together formed a combination of horrors which no pen can describe”

The Americans didn’t necessarily have to stay on the HMS Jersey, nor any of its sister ships which were eventually brought in once it ran out of space. The British soldiers holding them captive often attempted to bribe them with promises of land and money; the only price for their freedom and reward was that they renounce their allegiance to the United States and bow once again to the rule of King George. By all accounts, almost none of the more than 10,000 prisoners did so. Such was their belief in the American cause.

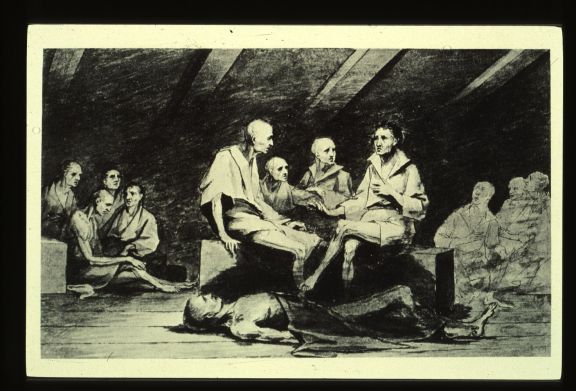

By 1780, prisoners were dying aboard the Jersey at a rate of roughly 8 each day. At least, that’s how many bodies were unloaded from the ship every morning at 8:00 AM. Corpses were brought up to the top deck as they were discovered, and left there until morning, when they were piled onto a wooden plank and lowered over the ship’s side to be buried in shallow pits on the sandy banks of Wallabout Bay. Sometimes, bodies would go weeks before being discovered, so dark were the prisoners’ quarters. The air was reportedly so foul that no flame would stay lit.

And since the dead were buried in mass graves only 2 or so feet deep on sandy beaches, storms and tides regularly uncovered their rancid and decaying corpses, adding an increased air of death and misery to the already-gloomy bay. No records were kept of the dead, and last rites were rarely performed before they were unceremoniously dumped into their pits. Most prisoners remain nameless; their families would never have the closure of knowing what had happened to them.

By the end of the war in 1783, it was estimated that roughly 8,000 men and boys had died of disease, starvation, and maltreatment aboard New York’s prison ships: that’s 8,000 out of the estimated 25,000 Americans who died in the entire war.

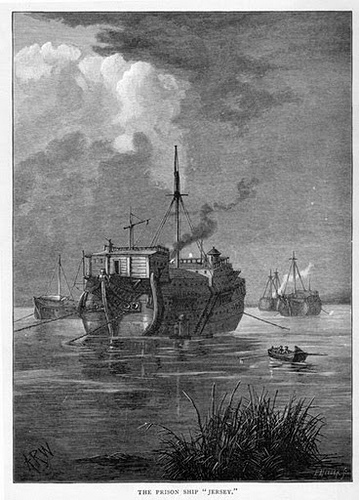

In the years following the Revolution’s conclusion, daily tides uncovered a seemingly countless number of skulls and bones on the shores surrounding Wallabout Bay. Skulls were said to litter the beaches as thick as a pumpkin patch, and children would kick them about like a ball. As Brooklynites collected more and more of the bones, calls began to ring out for a more respectful and honorable resting place for these most neglected of Patriots. Thus, in 1808, a crypt was constructed for the skeletal remains, almost none of which could be identified, near the bay. There they would rest in relative peace for another century.

During that century, arguments waxed and waned regarding the construction of a more fitting memorial to these glorious dead. The flame of patriotism was fanned, funds were raised, and in 1908, on a hilltop overlooking the bay where so many thousands of tales of misery were played out, a monument was erected to the Prison Ship Martyrs. Beneath the 100 steps leading to the soaring memorial column was constructed a spacious crypt. 20 slate boxes filled with the bones of the deceased thousands were placed in the crypt and sealed behind a bronze door. 20,000 New Yorkers and other dignitaries turned out on a cold, rainy November day to dedicate the memorial.

The dedication of the Prison Ship Martyrs Monument, November 14, 1908.

(NY Times, September 4, 2011 / Clinton Irving Jones, Fort Greene Park Conservancy)

But time has a way of erasing memories. As New York’s fortunes ebbed in the later decades of the 20th century, so too did the fate of the Prison Ship Martyrs Monument. A staircase and elevator which once ferried visitors to the column’s pinnacle were both removed in 1945. Vandals marred its base with graffiti and in 1966, the monument’s 4 large bronze eagles were removed to be restored, never to return (2 remain in storage and 2 are on display at the armory in Central Park).

As New York has gone through a bit of a renaissance in the past several years, the Martyrs Monument has not been entirely forgotten. Between 2006 and 2008, more than $5,000,000 was spent to restore the column and its surrounding plaza. Despite its restoration, however, the thousands who perished here and whose bones lie beneath our feet remain largely ignored by modern generations. In 2008, in celebration of the memorial’s centennial, only 200 people turned out in the park. Compare that to the 20,000 who flocked there in the rain a century before.

Inside the crypt, showing several of the 20 slate boxes which hold the bones of the prison ships’ thousands of victims.

(Photo by Sebastian Kahnert via http://www.brooklynpaper.com)

These men walked and fought alongside George Washington. They suffered and died in the name of American independence. They endured untold indignities, even in death. And this largely-forgotten memorial atop a hill in Fort Greene Park is among the most hallowed ground in this nation. We owe everything we have today to the ideals these men held so dear. And we owe them our respect and an immense debt of gratitude.

As a Brit I won’t say too much here except to that the working class of England at that time weren’t treated a whole lot better and so many of the British forces were pressed men. The real war is that between the haves and the have nots and I’m not sure how far that battle has gone. The real role of history is to moderate present actions and all people patriots or not should remember that.

Are you for real? All historical biases aside, those prison vessels were basically small-scale Nazi-era concentration camps. People were sent here to die and almost nobody left alive. Don’t even try saying the average Brit received the same treatment because it is grossly inaccurate.

Here lie the unknown dead…hundreds, perhaps thousands of men of all ranks who died on the Hell Ships run by the British in New York Harbor during the Revolutionary War. Many more died in other British Prison Ships in other locations such as Charleston, S.C. Yet it is here in New York City, that this unique monument, memorializes their sufferings, of those who served and were captured by the British, and imprisoned on their hell ships in NY Harbor during that great and terrible conflict so long ago. The British captives were must certainly not treated this way, and retributions and incriminations were sought by Congressional Oversight Committee, after that conflict, however one must dig deep into into U.S. History’s mysteries to seek the rest of that story.

Pingback: A Tale of Two Prisoners | CatholicVote.org

I have walked about this park countless times and never realized until now that this memorial column marked an actual grave. Thank you for enlightening us. I feel humbled and bit embarrassed by my ignorance.