In 1906, George Thompson rented out his summer home in Oyster Bay, Long Island, just as he did every year. This time, the renters were Charles Henry Warren and his family. With them, they brought a hired cook by the name of Mary Mallon. Come August, in rapid succession, Mrs. Warren, one of their daughters, and two maids fell ill with fevers. Shortly afterward, the gardener and another daughter caught the same sickness. It was ruled to be Typhoid.

Typohoid Fever was a dreadful and often deadly disease in 19th-century America. Spread through water and food sources, the disease would surely prevent George Thompson from ever renting out his house again unless he could pinpoint the origin of the disease and prove that the house was safe. To sniff out the source, Thompson hired a sanitation engineer by the name of George Soper. He immediately suspected the summer maid, Mary Mallon, as she would have been the one handling virtually all of the family’s food preparation.

Soper traced Mary’s work history back to 1900, and discovered that Typhoid outbreaks seemed to follow her wherever she went. 22 of her employers and members of their families had contracted the disease between 1900 and 1906, with at least one young girl dying. But Mary’s culpability couldn’t be proven without blood, urine, and fecal samples. And, perhaps unwisely, Soper decided to approach Mary directly at her current workplace to demand such samples from her. She reacted perhaps how any self-respecting woman would react: she refused vehemently, brandishing a carving fork, and chasing him out of the house.

Mary Mallon, all 190 pounds of her, had immigrated to New York in 1884 from Ireland, where she’d been born in 1869. She got a low-paying job as a domestic servant, but quickly found her talent in cooking, which also paid much better than other servants’ jobs. Being accused of carrying and spreading a feared disease, all the while being outwardly healthy oneself, would have been an understandably outrageous and inflammatory situation to be put in.

But Soper continued in his pursuit, bringing assistants and even medical examiners to Mary’s home in attempts to procure samples from her. Mary became increasingly suspicious and evasive, standing watch at her windows with her carving fork. When Soper returned with police officers and doctors, Mary charged them before vanishing from the house. Mary’s pursuers found footprints leading from her back door to a chair next to her fence. In her neighbor’s house, they found a piece of cloth caught in a closet door. Dr. S. Josephine Levitt described what happened next:

“She came out fighting and swearing, both of which she could do with appalling efficiency and vigor. I made another effort to talk to her sensibly and asked her again to let me have the specimens, but it was of no use. By that time, she was convinced that the law was wantonly persecuting her, when she had done nothing wrong. She knew she had never had typhoid fever; she was maniacal in her integrity. There was nothing I could do but take her with us. The policemen lifted her into the ambulance and I literally sat on her all the way to the hospital; it was like being in a cage with an angry lion.”

At Willard Parker Hospital, specimen samples were finally obtained from Mallon, and typhoid was found in her stool. She was quickly transferred to a quarantined ward of Riverside Hospital on North Brother Island in the East River. Word quickly spread of “Typhoid Mary,” the most dangerous woman in America.

But was this legal? Was it legal to hold a woman, against her will, labeling her as a menace to society? Mary didn’t think so, and in 1909, after two years of isolation on North Brother Island, Mary sued the New York Health Department. She began sending stool samples to an independent lab, which at no time could identify Typhoid in her system. Mary became convinced she was being wrongfully held.

Modern medical science remained in its infancy during Mary’s lifetime, and unbeknownst to her or to her doctors, she was actually the first healthy Typhoid carrier in America. It is suspected that she unknowingly endured a weak bout of Typhoid at some point in her life and built an immunity to it while still carrying the virus in her system. She was then able, especially as a cook, to easily transmit the disease to anyone eating her food.

Mary lost her court battle against the Health Department and was returned to her island prison. But the following year, in 1910, a new Health Commissioner agreed to set Mary free, provided she sign an affidavit promising to never work as a cook again. She eagerly agreed and was released into the city.

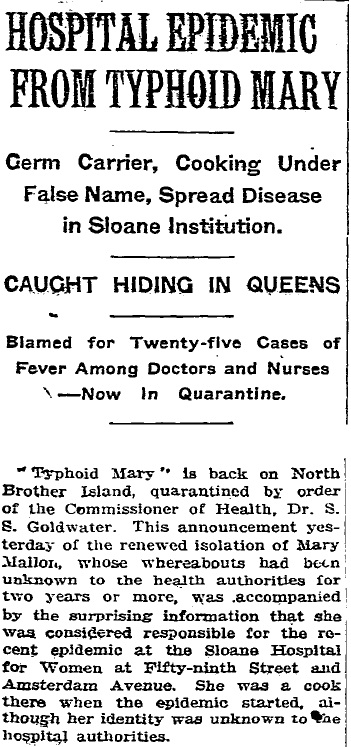

But working as a cook paid substantially more than working in other lines of domestic service, and Mary was soon tempted to return to her calling. In 1915, half a decade after Mary was released from North Brother Island, Manhattan’s Sloane Maternity Hospital suffered a Typhoid Fever outbreak in which 25 women fell ill and 2 died. It was soon discovered that a portly, Irish woman going by the name Mrs. Brown had recently been hired to work in the kitchen of the hospital. Mrs. Brown turned out to be none other than Mary Mallon.

Public opinion of Mary during her first round of isolation had been mostly that of pity: this poor immigrant woman locked away, desperately insisting on her innocence. But this time, she had known what she was doing. She had known she would be putting people at risk by cooking, but did it anyway. Her actions smacked of malice, and she was shown little mercy.

Mary Mallon was sent back to her cottage on North Brother Island. She would remain there for the next 23 years. She suffered a paralyzing stroke in 1932, and died on the island in 1936. Her body was cremated, and the ashes were buried at St. Raymond’s Cemetery in the Bronx.

Mary was ultimately responsible for sickening 47 and killing 3. She wasn’t even the deadliest Typhoid carrier of her day (an Italian immigrant named Tony Labella is said to have sicked 122 and killed 5) but her legacy endured. To this day, the moniker “Typhoid Mary” is used to refer to anyone who unknowingly passes a disease on to others. Few remember that Mary was a real woman, probably terrified out of her mind, unable to understand the harm she was causing, forced to spend her remaining days alone on a tiny island in the East River.

A sad and fascinating part of history.