The faint outline of the roof of the Grand Central Hotel remains on its former neighbor. Looking SW from Broadway at W 3rd Street. Image from Google Maps.

Today, if you stand at the intersection of Broadway and West 3rd in the Village, and look to the southwest, you’ll see a rather unassuming red brick post-modern apartment block. It is set back a few yards from the sidewalk, its lower floors shaded by a row of young trees. But if you step back, and count up to the 8th floor, you’ll notice something peculiar. The apartment block’s much older neighbor to the south bears an oddly-shaped scar on its exposed wall where the newer building is set back. A steep zig-zag almost like a Babylonian ziggurat in shape: this is theonly ghostly remainder of what was once New York’s largest and grandest hotel.

The Grand Central Hotel was opened to much fanfare on August 25, 1870. It had been built atop the lot once occupied by the 1850s “LaFarge House” hotel and its neighbor, the Winter Garden Theatre. Both had been devastated by fire in 1867, leading to their eventual demolition. With 650 rooms spread comfortably throughout 8 floors, the hotel was the largest ever constructed in New York, or even the United States, up to that time. The brick-and-marble palace awed visitors and reporters alike. A new standard for hotel comfort had been set.

But almost immediately, the Grand Central was plagued by tragedy. On May 30, 1871, less than a year after the hotel’s opening, a 35-year-old man checked in under the name “J.F. Hays” of Massachusetts. He was assigned to room 422, which contained a parlor, bedroom and bathroom on the building’s third floor facing Broadway. Early that afternoon, he rang the desk to inform them that he would not be attending dinner, but would like some toast and tea brought to his room. His wishes were fulfilled, and he was not seen again that night. At 10:00 the next morning, May 31, he rang the desk again, requesting a newspaper be brought to him. When a boy arrived at his room with the paper, he found “Mr. Hays” sitting on his bed wearing nothing but his nightshirt. His toast and tea hadn’t been touched. He took the paper and bade the boy not to bring anything else to him that day. Around 5:00 that afternoon, the maid arrived to tidy his room. Finding the door locked, she assumed the occupant was out and had left the key at the desk. She began making the bed, but while doing so, she glanced into the bathroom. There, slumped in the tub and covered with blood, was “Mr. Hays.”

He had likely been dead for hours, as rigor mortis had set in. The maid, in a panic, fetched the hotel’s supintendent. When he arrived, he inspected the body. One small bullet hole could be seen, about three inches below his nipple and pointed downward toward his abdomen. Death would have been quick. A five-barrel revolver was found wedged beneath his corpse. A suicide note was found in the room, which revealed his true name to be George E. Hathaway of Rutland, Vermont. George had studied briefly at both Harvard and Tufts Universities in the 1850s before moving to Rutland to apprentice as a lawyer. He had been married to a young lady by the name of Emma Dana in 1864, and the pair had birthed a child, Mary, in 1866. But Mary quickly succumbed to scarlett fever, and the fever then spread to Emma. Both were dead by the end of October of that year. By all accounts, George then sank into a deep depression from which he evidently never recovered. He requested that he be buried next to his wife and daughter.

The following year, 1872, the Grand Central suffered perhaps its most famous tragedy: the murder of James Fisk by Edward Stokes. Fisk, a prominent New York businessman, had scandalized New York society when he began dating infamous actress and reputed prostitute Josie Mansfield, going so far as to build her an apartment adjacent to his Erie Railroad offices above the Grand Opera House on 23rd Street, which he also owned. But in time, Josie fell in love with Fisk’s younger and more handsome business associate Edward Stokes, who left his wife and children to be with Josie. The new couple then attempted to extort money from Fisk by threatening to publicly release letters Fisk had written to Josie, which allegedly proved Fisk’s legal wrongdoings. Much to their chagrin, Fisk refused to ante up even a cent, and the ensuing legal battle erupted into a fiery courtroom scandal.

Both Stokes and Fisk sat on the witness stand for Fisk’s libel suit from 10:00 until 2:00 on January 6, 1872. Two hours after their release, Stokes was seen strolling the corridor along the second floor of the Grand Central Hotel. Dressed in a dapper light-colored suit, he aroused no suspicion among the well-heeled guests of the hotel. At 4:00, James Fisk pulled up to the building’s northern Broadway entrance in a carriage. When he reached the midway landing of the staircase, he looked up: there stood Edward Stokes with a pistol in his right hand. He fired once, hitting Fisk in the abdomen as he crumpled to the floor. He tried to pull himself to his feet, but Stokes fired again, this time hitting him just above his left elbow. Fisk dragged himself back down the stairs, where he collapsed on the stoop.

Stokes quickly tossed the still-smoking Derringer onto the sofa of the ladies’ lounge and casually walked toward the hotel’s rear exit to Mercer Street. But as he approached the door, a cry went out from upstairs that a man had been shot. Stokes tried to run, but as the hotel’s proprieter shouted “Stop that man!” Stokes slipped, fell, and was seized by several male hotel employees, who held him down until the police could arrive.

Fisk, meanwhile, was carried upstairs to room 213, into which a doctor was called urgently. Though his arm wound was largely benign, the first shot to his abdomen appeared to be fatal. He rallied for several hours, allowing for his lawyer to be called in to take his sworn statement of the events which had transpired.

Fisk died later that night. Stokes was taken to the Tombs prison, where he bribed his way to an extravagant cellblock lifestyle, ordering scented bathwater and meals from Delmonico’s. His first trial resulted in a hung jury, possibly due to one of more jurors being bribed. His second trial saw him convicted of murder in the first degree, which carried a death sentence by hanging. But this verdict was appealed and eventually overturned. On trial for a third time, Stokes was convicted of manslaughter and sentenced to six years at Sing Sing Prison. Josie fled to Paris, where she spent most of the rest of her (long) life. She died there in 1931.

About a block away from the Grand Central stood the depraved “Canterbury Variety Theatre,” whose proprieter, Elisha Gregory, had vehemently defended it against an onslaught of efforts by the city’s government to close such “concert-saloons” in the 1870s. In December of 1872, an article appeared in an evening paper denouncing the Canterbury and calling on the police to shut it down. Enraged, Gregory blamed former New York Herald reporter George Wilcox for the article’s inception. By chance, Gregory ran into Wilcox, who was standing outside the entrance to the Grand Central Hotel on the evening of December 21st. He accused Wilcox of writing the article, but Wilcox denied any knowledge of it. He then turned into the hotel away from Gregory, who followed him into the lobby and punched him. Wilcox fled into the hotel’s barber shop as Gregory pulled out a pistol and gave chase. He slipped and fell, however, just as a young man named Theodore Williams, who had just received a shave in the barber shop, walked out of the door. As Gregory hit the floor, his pistol went off, hit Williams in the foot. The police shortly arrived, and Gregory was hauled off to the Jefferson Market Police Court on 6th Avenue.

For just over a year, the Grand Central operated in relative peace, becoming the premiere hotel of the burgeoning city. But a blurb in the New York Times in February of 1874 shows that tragedy continued to befall the hotel:

And again in 1877:

In April of 1877, a hotel waiter by the name of George Peters arrived late for tea service in the dining room. He had a reputation for being late and a drunk, and had been fired and rehired multiple times over the previous months. After a vulgar verbal argument, he was again discharged by assistant head waiter James Larney. At noon the next day, however, Peters returned to the hotel’s dining room, where Larney was helping prepare for the day’s lunch. Peters pulled out a seven-chambered pistol and fired three shots at Larney in rapid succession. The first bullet struck his thigh, the second blew away his thumb as he attempted to shield himself, and the third passed through his clothing, grazing his chest. He sank to the floor, and Peters was quickly arrest by a passing policeman who had heard the shots. Larney survived. Peters was arraigned for attempted murder at Jefferson Market Courthouse.

Suicide returned to the Grand Central just months after the Peters shooting. 42-year-old James A. Grover, who had lived at the hotel for about a year, was found dead in his room by a chamber maid on August 4, 1877. His death was apparently the result of an overdose of chloral-hydrate. A nearly-empty bottle of the drug was found near his bed, and multiple empty bottles of it were found in drawers in his washroom. He left no note and no indication as to why he decided to end his life in such a way.

Around 10:00 on the night of June 28, 1878, a 50-year-old resident of the hotel by the name of J.H. Taylor invited a 10-year-old girl to his chambers to “show her some nice pictures.” The girl was popular and well-liked among the residents of the hotel, and such a request was not out of line coming from Taylor, who had lived there as well as the girl’s family, for years. Once in his room, however, Taylor began to “caress and fondle the child until she became alarmed at his rudeness,” and attempted to flee. Taylor grabbed her, offering her gifts and money to stay with him, but she continued to try to run, at which point Taylor knocked her to the ground and “attempted to commit a gross outrage upon her.” She screamed, which startled Taylor enough to release her, and she ran crying to her mother’s room. She related her experience to her mother, who in turn passed the story to the girl’s father. Enraged, he pondered shooting Taylor, but thought better of it and called the police. The following morning, Taylor appeared in the crowded hotel dining room for breakfast, acting as if nothing had happened. The girl and her family then entered the room. Her father grabbed Taylor by the collar, while her 22-year-old brother began beating the man about the face with a rawhide whip. The girl’s mother, when other boarders attempted to intervene, announced to the crowd what Taylor had done to her child. The other tenants quickly turned on Taylor, who was rescued only when the hotel’s police officer arrived and calmed the fracas. Taylor sat down to finish his breakfast, to the jeers of his neighbors. Shortly thereafter, his baggage was packed and he fled the Grand Central, threatening to sue the girl’s parents.

Six years after the cowhiding, on July 26, 1884, a 35-year-old man checked into the Grand Central under the name B.F. Estes. He was shown to room 551 on the 4th floor and was otherwise left alone. At 10:00 the next morning, a chamber maid discovered him moaning in a pool of blood on his bed. Estes had shot himself just behind his right ear with a 32-calibre pistol. On his bedside table in the hotel were found two brief notes: one to his father, and one to his fiance.

He clung to life, however, and was brought to St. Vincent’s Hospital, where a surgeon removed several shards of bone from the bullet hole. This removal jolted Estes back to consciousness enough to ask the doctor to have his friends brought to the hospital. He explained that he tried to kill himself “because he suffered from a mental and nervous disorder of an epileptic nature,” and he feared this would ultimately evolve into complete insanity. By mid-afternoon, Estes had lapsed back into unconsciousness. He succumbed to his wound that night.

80-year-old Noah Hunt moved into the Grand Central Hotel back in 1882. He kept to himself over the following four years, becoming known as a “Hotel Hermit.” He had amassed a fortune in excess of $3,000,000 in the iron and stocks business throughout his life, but had never lived anywhere but in a hotel, and he remained a bachelor all his long years. Early in the morning on November 12, 1886, Noah died of bronchitis in his room at the Grand Central.

Twenty years of relative peace passed for the hotel, and it changed its name, albeit subtley, to the Broadway Central Hotel. But on the night of April 11, 1906, the building itself came under attack. A “fire bug,” as Mercer Street Police Captain Stephenson put it, had set three separate fires in the building, resulting in an evacuation of its roughly 500 occupants. At 8:35, pile of oil-soaked rags had been discovered burning in the engine room by steward Jack McCormack, but he luckily snuffed them out before the flames did much more than char some woodwork. An hour later, a “negro bell boy” by the name of Samuel Johnson found the curtains ablaze in a second-floor suite. He ripped the curtain rod down and called for help. He and a bucket brigade of chamber maids was able to put the fire out within minutes. Finally, near 11PM, as a detective inspected the previous two fires, a hotel guest discovered a burning pile of clothes in a fifth-floor bathroom. Luckily again, they were able to be quickly put out before they caused significant damage.

But it was clear that someone had a vendetta against the Broadway Central and its tenants. When interviewed, multiple guests reported seeing a young man around the hotel earlier in the day who fit the description of noted arsonist Edward Farley. He had previously worked at the Central in 1897, and a small fire discovered there that year was traced back to him. In 1902, he had been employed at the Astor House as an elevatorman and was caught setting three fires in that hotel in one day. When apprehended for the Astor House fires, he admitted to having set eleven such fires in various hotels around the city over the years, and was sentenced to the Elmira Reformatory in western New York State. He had apparently been released very shortly before the three fires were set in the Broadway Central, and remained the prime suspect. Another theory, however, was that the fires were set by a recently-fired Greek employee of the hotel who had loitered about the building that day until being thrown out by a policeman. Also a possible cuprit was another former employee who was known to have a working knowledge of the hotel’s fire alarm system. No employees had called the fire engines, but they had received an alert from the hotel’s fifth floor, where the alarm is encased behind glass which would ordinarily be broken to be rung. But the glass in this case had been carefully removed in one piece – a suspicious bit of evidence. Yet another hypothesis, though one which received little credence, was that the fire bug was a “negro” seeking retaliation against the hotel’s cigar salesman David Oliver, whose wife had recently caused the arrest of a “negro” man who had struck her face on an elevated train. But the police largely ignored this lead. The hotel was stocked with officers that night and the next, but no more fires were discovered. And the arsonist was never apprehended.

One of the residents evacuated during the arson scare was Spaniard Manuel Martinez, who had already been living at the Central for 25 years at that point. Born in Granada in 1823, Manuel was a voracious reader. He devoured the works of Voltaire, Rousseau, Plato, and Aristotle. “As a minor,” he is quoted as having told his nephew, “at the age of 16 in fact, I left my home in Granada and commenced to travel … I went to Austria, to Germany, France, Russia, England, and to Rome. And everywhere I found the people blindly ruled and oppressed by religion. I visited the Holy Land of the Old and the New Testament. I grew no more friendly toward religion. In fact, I became an atheist. I tried to escape from a religious atmosphere in America, in Mexico, Canada, and Cuba. It was the same. I became disgusted with the childishness of the faith and beliefs and superstition I found in men.”

He moved to New York in 1876 to take over a banking business left to him by a deceased brother, but his disdain for religion and its adherents pushed him into seclusion. Some time around 1881, he got a small room at the Grand Central and filled it with “the precious books of truth and philosophy,” over which he pored daily, rarely leaving even for meals. He resisted learning English so that he might better remove himself from society and its theistic ills, though he did keep in contact with two nephews who lived in the city. When he fell ill in June of 1911, they urged him to see a doctor. His reply was simple:

He passed away in the hotel, in the company of his nephews, on July 30, 1911, at age 88.

By the 1920s, the neighborhood surrounding the Broadway Central had changed drastically. Long gone were the wealthy, elegant ladies and gentlemen who had called lower Manhattan home when the hotel was built half a century before. It was sold in 1923 to an investor by the name of Louis Kramer and re-sold just months later to the Manischewitz’s, a wealthy Jewish family who renovated the building and transformed its cafe into one of the premiere Jewish banquet halls and buffets in the city.

In 1924, 30-year-old Samuel Brown was the manager and part-owner of the Grand Street Garage at 3 Broome Street (which has since been replaced by public housing towers) and a father of five. On Saturday, May 24 of that year, he bade his wife good night, telling her he was going out to collect bills for the garage, as he did many nights. In reality, he snuck away to the Broadway Central Hotel to meet up with 24-year-old Ms Dorothy Brown of French Canada, with whom he was having an affair. The two went out for much of the evening, but returned to the hotel after midnight. Shortly thereafter, their neighboring tenants on the 4th floor heard a gunshot ring out. The hotel’s night clerk was notified, and a police watchman was called for to investigate.

Upon entering the room, Officer Catewood found Samuel lying shot and bleeding on the floor. Dorothy was sitting on the windowsill, slowly smoking a cigarette. When asked what happened, she told Catewood that Samuel had shot himself, whereupon Samuel gasped aloud, “That woman shot me!” Dorothy refused to reply to his accusation until the officer demanded she speak. “Well, if I did, it was accidental.” She was taken into custody while Samuel was carried off to St. Vincent’s Hospital, where he shortly died. When his wife came to identify the body, she said, “He got just what he deserved.”

The old hotel was obtained by the U.S. army soon after the Brown murder, and would be held by them until the close of World War II. At that time, it was completely refurbished and re-opened as a hotel once more. And it was miraculously able to stay out of the headlines for several years thereafter.

But in the early hours of December 21, 1963, in bitterly cold and windy weather, a fire erupted on the building’s 5th floor. In short order, all 200 residents were evacuated, and two fire alarms were sounded and the flames creeped all the way up the 6th and 7th floors. Thankfully, once the fire engines arrived, the flames were quickly gotten under control, and the blaze was out by 6:15AM. Much of the damage was superficial and the hotel re-opened after relatively minor refurbishment.

But New York in general was in a bad way by the end of the 1960s. And the nearly century-old Broadway Central Hotel followed the city on its downward trajectory. Sometime around 1970, the hotel was sold to new property managers who elected to transform the once-elegant inn into a “welfare hotel,” taking in the city’s most desperate and depressed residents whose $5 nightly rent would be paid by the government (a secure source of income for the owners). The refined parlor rooms once rented by New York’s elite society members were now filled with more than 300 impoverished and destitute families, often times packed seven or more to a room. Children by the dozens ran virtually untended through the stairwells and hallways, wreaking havoc wherever they went.

Drug use, prostitution, and theft were but the most obvious of problems running rampant throughout the Broadway Central during those dark years, as was glaringly reported by the New York Times in a January 1971 exposé. And the pall grew even more oppressive in November of 1970, when 4-year-old resident Gerald Wilmore fell (or was pushed) down an open stairwell to his death. The Central was at its lowest of lows.

Within months of the scathing Times report, it was announced that the Broadway Central would be emptied of its welfare families and returned to its original use as a hotel. The families would be sent to newly-built public housing projects elsewhere in the city. The owner is quoted as having said “he hoped to attract more ‘working-class people’ as tenants after the welfare families moved. He renamed it the University Hotel, riding on the coattails of nearby New York University, and tried to return it to some semblance of normalcy.

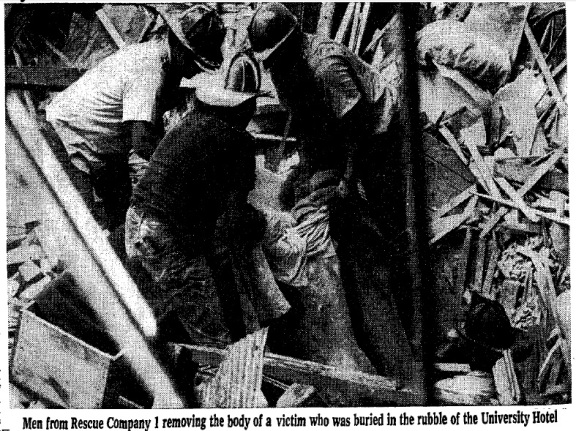

A photo showing the large section of the hotel which collapsed into the street.

NY Times, August 4, 1973

But the owner was guilty of having neglected a laundry list of structural code violations for which the building had been cited over the previous years. Exterior walls were buckling, and load-bearing walls in the basement had recently undergone unauthorized construction work, weakening them to a dangerous state. Early on August 3, 1973, guests staying in the hotel began hearing strange noise and feeling ominous rumbling sensations emanating throughout the building. Most chose to voluntarily evacuate, and by early afternoon, police officers were going door to door, ordering people to flee. Just after 5:00PM, the walls gave way. Thousands of pounds of brick, wood, and stone came crashing down upon Broadway, forming debris piles up to twenty feet deep.

Over the next several days, four bodies were pulled from the rubble. The rest of the structure was deemed unsafe, and all but a portion of its marble facade was torn down, officially ending the 102-year life of the Grand Central Hotel.

Fire Engine 24 holding “Dino,” a dog they rescued from the rubble of the collapsed hotel. Dino’s owner gave him to the firemen as a thank-you for their bravery in digging through the dangerous site.

NY Times, August 8, 1973

A criminal trial was held over the following years, with blame being pinned alternatingly on the building’s owners for ignoring code violation warnings, and on the city of New York for not following up on them.

83-year-old Samuel Steinhart survived the collapse, only to be beaten and stabbed to death by an 18-year-old robber in his next home.

NY Times, June 3, 1974

The Broadway Central Hotel’s hundreds of surviving residents were cast out into an unfriendly city. Roughly 150 of them moved into the Hotel Martinique at Broadway and 32nd Street, but many were elderly and impoverished, and most had lost nearly all of their earthly possessions in the disaster.

Eventually, the hotel’s remaining shell was torn down, and the neighborhood began to have a resurgence. Once again, the young and wealthy of New York stroll the streets of Greenwich Village, most unaware of the many dramas and tragedies which occurred in hotel whose only remaining physical legacy is a ghostly outline on a neighboring wall. The Grand Central, once America’s premiere lodging house, is exiled to history.

Thank you for all your time and research! I’ve just found your blog and look forward to reading more. This was so interesting!

Pingback: Evelyn McHale: A Beautiful Death on 33rd Street | Keith York City

Pingback: 1874: The Cider Press Dogs at the Corner of Broadway and Houston | The French Hatching Cat

This is a fascinating story………Thank You!

Great stories! Thank you for your research.

Thanks again for reading! This article in particular was a surprise and a joy to research. I had known about the hotel, mainly because of its collapse in the 1970s. But I had no idea it had such a sordid past otherwise until I started researching it in the NY Times archives. I love when history unfolds so unexpectedly like that!

I appreciate the amount of research and effort you put into this, but I also find it weird that you call the hotel’s years as a site of welfare housing its darkest. It seems that many of its years were dark–the difference is only in the class of people who occupied it.

Hi and thanks for reading! The hotel did indeed have many dark days in its past, but for the most part, they were isolated incidents within a hotel that was otherwise occupied by upwardly-mobile families and individuals for whom crime and death was the exception, not the rule. The hotel’s years as a welfare home were, as far as I could tell from what I researched, plagued by drug abuse, severe poverty, and violence, all of which was compounded by sctructural neglect which would ultimately lead to the building’s collapse. Calling these the hotel’s “darkest days” is a matter of my opinion. However, I based it on an overwhelmingly negative amount of evidence supporting that assertion, and not merely on the class of the individuals living there at the time. I apologize if I implied anything offensive in my writing, and I hope this clarifies my choice of words to some extent. Again, thanks for reading and feel free to write any time!

-Keith

brilliant read, thank you very much for all your efforts cant wait to see what else i can find 🙂

Awesome research & writing, just a heads up the 2nd photo “The Grand Central Hotel, ca 1880” is actually after it was changed to the Broadway Central, check out the center flag & the upper left side of the building, I thing that would be after 1886 sometime. Either way I loved reading it.

You’re probably correct – sometimes I get so bogged down in writing, editing, re-writing, and re-editing that by the time I get to the photo insertion part of my process, my brain is jelly. I’ll take a look at it and try to make the appropriate edits today! Thank you for reading!

-Keith

This was so awesome!! It makes me wish we’d have more respect for old architecture! Ugh, I wish I could have seen inside this building. Thank you for writing this.

I found a typo – you meant to type hit, not his – The but about Elisha Gregory.

Theodore Williams, who had just received a shave in the barber shop, walked out of the door. As Gregory hit the floor, his pistol went off, his Williams in the foot.

I think I remember noticing that typo long ago, but I obviously never made the effort to go in and correct it. Thank you for reminding me! I’ll get it taken care of ASAP! And thanks for reading – hope you enjoyed!

-Keith

This article was fas-ci-na-ting!

Thank you

Excellent job on this history of the old Broadway Central, Keith. I knew the place had a bit of “history” but this was just incredible reading. Thank you for the time and effort put into this – I know it’s a very time consuming process as I did quite a bit of research on the place myself a few years back for a few items I did on the Mercer Arts Center and The St. Adrian Company which were both located there in the late 60’s until the collapse.

(Mercer Arts Center)

http://thisaintthesummeroflove.blogspot.com/search?q=mercer+arts+center

(St. Adrian Company)

http://thisaintthesummeroflove.blogspot.com/2008/12/giving-up-ghosts-of-st-adrian-company.html

Keep up the great work!

Fascinating and truly well-written. Thank you for writing this! Looking forward to reading more of your work 🙂

Thank you! I hope to get some new posts up soon. Stay tuned!

-Keith